An enormous 3,000-year-old earthen platform topped with a series of structures, including a 13-foot-high pyramid, has been identified as the oldest and largest monumental construction discovered in the Maya region, according to a paper published today in the journal Nature.

The temple site in Tabasco, Mexico, was discovered by archaeologists from the University of Arizona and an international team during an expedition in 2017. The team then excavated the site and radiocarbon-dated 69 samples of charcoal to determine that it was constructed sometime between 1,000 to 800 B.C. Until now, the Maya site of Ceibal, built in 950 B.C., was the oldest confirmed ceremonial center. This oldest monumental building at Aguada Fénix turned out to be the largest known in the entire Maya history, far exceeding pyramids and palaces of later periods.

Aguada Fénix’s design suggests that early Mayan societies were fairly egalitarian and didn’t have a powerful ruling class.

It’s the latest discovery to support the emerging view that some of the earliest structures built in the Maya region were significantly larger than those built more than a millennium later during the Classic Maya period (250-800 A.D.), when the empire was at its peak.

The Mayan civilization flourished in the Americas before European colonization. The Maya built huge cities and had an advanced knowledge of astronomy, but their civilization collapsed around 800 AD.

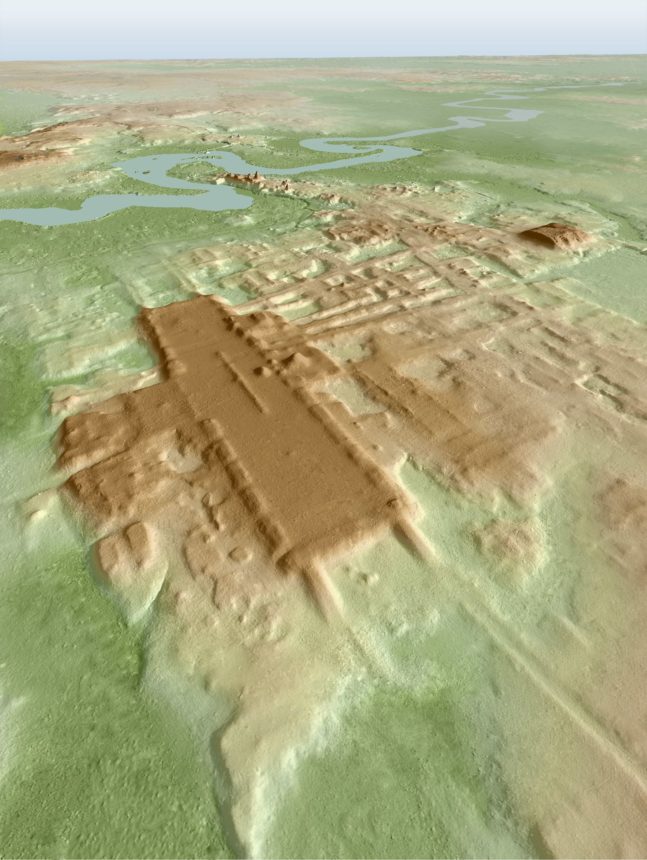

Daniela Triadan at the University of Arizona in Tucson and her colleagues have described for the first time how they conducted an airborne survey using lidar, a remote sensing method that uses lasers to create a 3D map of the surface below, to scan the ground in Tabasco state in south-east Mexico.

From the ground, it’s impossible to tell that the plateau where this site was discovered hides something extraordinary, the research team said. However, from the sky, with laser eyes, and beneath the surface, with radiocarbon dating, it became clear just how historically important the location was.

They found 21 sites for conducting Mayan ceremonies, all centered on rectangular earthen platforms running roughly north to south.

(Photo courtesy of Takeshi Inomata)

Researchers say the finding could dramatically transform the way archaeologists understand the timeline of the Mayan civilization.

Previously, it was believed that the Mayans developed their civilization slowly between the years 1,000 and 350 B.C. during a period known as the Middle Preclassic, with people living only in small villages as they began to transition from hunting and gathering to growing maize and using pottery.

But the newly discovered monument, dubbed Aguada Fénix by the researchers, challenges that consensus. The structure, which the researchers say was likely used as a ceremonial center, was built during the same time period but is nearly 4,600 feet long, 30 to 50 feet high and features nine different street-like causeways that were connected to the overall structure by a series of ramps.

The team estimates that between 3.2 and 4.3 million cubic metres of earth were used, requiring 10 to 13 million person-days of work. “It would have taken probably thousands of people,” says Triadan.

No residential buildings have been found on or around the structure, so it is unclear how many people may have lived nearby. But the large size of the platform leads archaeologists to think that the builders of Aguada Fénix gradually were leaving their hunter-gatherer lifestyle behind, likely aided by the cultivation of corn—evidence of which also has been found at the site.

The flat and open design of Aguada Fénix seems to have been built with egalitarianism in mind. “The whole construction itself seems to be this communal open space,” says Triadan.

There is no sign of monuments made for members of a powerful ruling class, such as large statues, Triadan says. In contrast, later Mayan pyramids were built by a society that had acquired a powerful ruling class who stood at the top of the pyramid, meaning others had to look up to them.

The fact that monumental buildings existed earlier than thought and when Maya society had less social inequality makes archaeologists rethink the construction process those sites went through.